WOODCARVINGS: ON THE VERGE OF DISAPPEARANCE

|

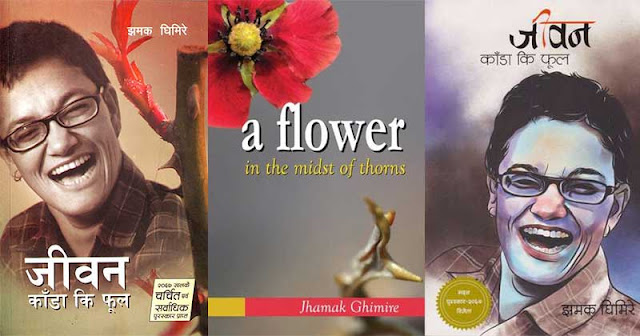

| Ratnaman Bajracharya is working on an enlarged table which was ordered by a foreign tourist. Photo: LB Thapa |

The history of Nepali woodcarvings was extremely rich during the Licchavi period (300-897AD). Wang Hsuan Tsang, a great Chinese monk and traveler, had visited Kathmandu during the reign of Licchavis. He had documented the richness of woodcarvings in Kathmandu. He wrote in his memoir in AD 643, “The people of Kathmandu are skilled in arts. Their houses are made of wood and richly carved” Through his description, it is evident that woodcarvings in Kathmandu were ahead of time. Historical facts suggest that Kathmandu was much ahead in the art of woodcarvings in the region. The rich history of woodcarvings took a flight from the 13th to 18th century Malla period. There was a time when woodcarvings in Kathmandu had attracted many artisans and scholars across the world.

In the course of time, many outstanding pieces of woodcarvings were lost by fires, earthquakes and foreign invasions. Despite the loss, some fabulous monuments are still left in the capital, which bore remarkable history and artisanship of its time. Kasthamandapa, a wooden mansion in Kathmandu, was built before 1143, which manifests the glory of rich woodcarvings. Nine-storey Basantapur Palace, Hari Shankar temple in Patan and Machhindranath temple in Bungamati, and Durbar square are some historical monuments, which are enough to prove Nepal’s supremacy in woodcarving in the past. Unfortunately, many of these monuments have been badly damaged in the earthquake on 25 April 2015. Hopefully, in a concerted effort of the government, Nepali artisans will be able to restore the lost glory of woodcarvings.Such a rich tradition of woodcarvings is now on the verge of disappearance. The number of skilled artisans is fast reducing, as younger generations are reluctant to adopt woodcarving as a profession. Unlike university graduates, skilled woodcraft artisans are not produced by any college and university in the country. Woodcarving is a family tradition and the art of woodcarving is handed down from one generation to another. The young members grow in the family looking at the elders who put their heart and soul together to create masterpieces.

However, nowadays time has changed. The young generations of today do not show much interest in traditional home businesses like woodcarving, stone sculpturing, goldsmith, ironsmith, pottery, traditional music and so on and so forth.

All photos by the author

At a time when traditional skills stand on their last leg, there are some handful of people, who can be counted on our fingertips, have resorted to keeping traditional skills alive. This scribe recently met a local woodcarver who was committed to carrying on the rich knowledge of woodcarvings despite several obstacles. His name is Ratnaman Bajracharya. His unmatched skill at woodcarving is simply astonishing and unparalleled.

“Woodcarving is our traditional family business. Generations of my family were involved in this form of traditional business. I got into woodcarvings ever since I was a tiny toddler. As a child, I would play with woodcarving tools and my favorite playmates were the idols of gods and goddesses. I would play with the idols of gods and goddesses as they were strewn everywhere in the house,” said Bajracharya with a broad smile on his face.

Ratnaman Bajracharya is originally from Lalitpur, Gungamati, ward number 2. His parents, brothers and sisters live in Gungamati, Lalitpur and many of them are still carrying the traditional business of woodcarvings. Mr. Bajracharya is the only member of the family who left Gungamati to make Pokhara his home. This came as a big surprise for the family as no one had ever thought of anything like that before. Generations of their families lived in Lalitpur and continued their family business. Lalitpur was their forte where they earned their livelihood and public recognition as artisans of par excellence. Therefore, Mr. Bajracharya’s decision to migrate to Pokhara was unexpected and shocking as well.

“At first my parents and brothers were vastly surprised when I disclosed my decision of migrating to Pokhara,” said Bajracharya and continued. “As an artisan, I was more creative in the family. From the early on I had carved a niche for carving outstanding designs on doors, windows, columns, struts, and balustrades. I could also make the idols of various Hindu gods and goddesses with remarkable precision and accuracy. I was, though still young, an important artisan in the family. Therefore, when I said I would start woodcarvings in Pokhara this came as a big surprise for my family”.

When asked why Mr.Bajracharya migrated to Pokhara when he had already well-established business and public recognition in Lalitpur. Upon this, he said: “In 1993 for the first time I had visited Pokhara. I knew a prosperous Newar community living in Pokhara since time immemorial. However, I noticed that not a single Newar was involved in the woodcarving business in Pokhara. I immediately took a vow to become the first person to introduce woodcarving tradition to Pokhara”.

It was a gamble to come out of the comfort zone and take an unnecessary risk by going to a place where there was no market for woodcarvings. When Mr.Bajracharya had decided to migrate to Pokhara, even his wife was skeptical about the success of their venture in Pokhara. It was difficult for a mother of two sons to leave behind the family’s security net and go to a new place. Despite all odds, Mr.Bajracharya had decided to give it a try.

“I knew I was taking a risk, but I was thinking differently. Without a doubt, Kathmandu is the hub of woodcarvings. However, I wanted to see the art of woodcarvings flourishing out of the Kathmandu valley as well. Why such a great art be confined in the capital alone! More than becoming commercially successful, my real intention was to establish the rich tradition of woodcarvings in Pokhara as well. Hence, in 1993 I opened Siddhi and Ratna Woodcarving in Pokhara with a bang”, revealed Mr. Bajracharya.

Mr.Bajracharya’s intention was novel and he wanted to spread the knowledge of woodcarvings in Pokhara. However, even after spending several days, he was not able to sell even a single item he had produced. “I had poured all my skills and made some items with rich embellishments and intricate designs on windows, doors and tables but there were no buyers of my art. This was enough to demoralize an artisan who was just trying to make a living in a new place,” added Bajracharya.

Mr. Bajracharya’s early foray into selling embellished windows, doors and tables could not bring critical success; and there was a time when he had to struggle to pay room rent. On top, his two sons were growing and so were the family expenditures. Pressing financial needs forced him to visit furniture shops and request them to sell the items he had made. “It was truly a very hard time for me and my family. Literarily speaking we were passing through a hard time. If there was anyone in my place he would have given in, but I was not ready to submit without a fight. I wanted to prove myself as an artisan of worth”.

Mr.Bajracharya continued his battle to survive. He trusted his guts and ability to produce the best of the woodcarvings. He visited government offices, construction sites and spoke with people about the woodcarvings. He would also invite them to his workshop and show what he had produced.

Eventually, Mr.Bajracharya’s efforts bore fruits. Gradually Pokhareli people started showing interest in his skill and Mr.Bajracharya started getting orders from different walks of people. “Looking at my initial success other woodcarvers did also come to Pokhara from Kathmandu. Today there are six woodcarvers in Pokhara who originally came from Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur” said Bajracharya.

Over the last decade, the rich tradition of woodcarvings has been losing its ground fast. The younger generations are not interested in carrying on the traditional profession of woodcarvings. “The numbers of Silpakars are decreasing every passing year. Young boys and girls who study in colleges and universities do not have the patience to spend hours honing their skills of woodcarvings. I tried my best to encourage my sons and daughter to learn the art but they flatly refused. My eldest son is studying engineering and my daughter is nursing. This is the story of almost all artisans’ families. In a situation like this I am much worried how the glorious history of Nepali woodcarvings will survive in future” laments Bajracharya.

Today Silpakars are facing many problems. The urban housing system has reduced the use of woodcrafts. Modern-day houses have more demand for synthetic doors and sliding windows. They don’t need any artistic designs on their doors and windows. At the same time, the supply of sal wood has been reducing every passing day. There is Indian and Malaysian sal wood available in the Nepali market, but these woods are not preferable by many artisans. Nepali sal wood is the first choice of all artisans for the best result.

Due to rapid urbanization, the demand for well-crafted wood items like idols, windows, doors, tables, etc. has shrunk largely. There is little export, which is not enough to provide financial independence to artisans. “For the last two decades or more I have been working as a full-time artisan, but I don’t have a house of my own in Pokhara. However, I do have my ancestral house in Lalitpur, but not in Pokhara. Mine earning from the woodcarving has helped educate my two sons and one daughter and I am happy with that” deplored Bajracharya.

The reality is that the lifestyle of traditional woodcarvers has not improved. However, those middlemen who collect finished products from the artisans and sell in foreign markets have prospered. There are some companies, which pay paltry sums of money to the artisans and sell their labor to the international market at higher prices. Thus, nowadays more and more artisans are not keen to involve their sons and daughters in this profession. As a result, there is an acute shortage of skilled woodcarvers in the country. Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, and Lalitpur are the hubs of woodcarvers, but nowadays even there, the numbers of traditional artisans have drastically reduced.

The government must wake up from slumber before it is too late. Traditional woodcarvers should not let be exploited at the hand of woodcarving industries and the middlemen. Woodcarvers’ families should get special state benefits and they should be encouraged to continue age-old tradition without any worry. If the woodcarvers and their families feel secure in their profession only then the rich tradition of Nepali woodcarvings can restore its lost glory for which Nepal was famous in the world.

|

| LB Thapa is a Pokhara-based freelance writer and author. |

LEGAL

WARNING

All rights reserved. No articles and photos published in this blog can be reproduced without the prior written permission of the author. Legal action will be taken immediately if any articles or photos are reproduced without the author’s knowledge. However, articles or photos can only be reproduced by duly mentioning the author’s name and the blog's name (read2bhappy.blogspot.com). The author must be informed by sending an email. All articles and the photos published in this blog are the copyright property of LB THAPA.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment